Originally published July 28, 2021 @ 7:08 pm

When working with application logs and other text files, it is often useful to view the contents of different source files side-by-side. Here we will take a quick look at various command-line methods for joining data columns from different files.

Let’s start with a simple example: we have these three files:

| al.txt | peggy.txt | marcy.txt |

Date Volume 2021-01-01 9827 2021-01-02 8372 2021-01-03 6399 2021-01-04 8726 2021-01-05 6882 | Date Volume 2021-01-01 8722 2021-01-02 2653 2021-01-03 9876 2021-01-04 2763 2021-01-05 8733 | Date Volume 2021-01-01 2762 2021-01-02 7622 2021-01-03 6523 2021-01-04 8725 2021-01-05 4265 |

We need to merge these three files into a single file that looks like this:

Date Al Peggy Marcy 2021-01-01 9827 8722 2762 2021-01-02 8372 2653 7622 2021-01-03 6399 9876 6523 2021-01-04 8726 2763 8725 2021-01-05 6882 8733 4265

Because the key column is the Date and all the dates are in sequence across the three files, we can use something simple like paste or pr:

paste -d' ' al.txt <(awk '{print $2}' peggy.txt) <(awk '{print $2}' marcy.txt) | column -t

Date Volume Volume Volume

2021-01-01 9827 8722 2762

2021-01-02 8372 2653 7622

2021-01-03 6399 9876 6523

2021-01-04 8726 2763 8725

2021-01-05 6882 8733 4265

pr -mts' ' al.txt <(awk '{print $2}' peggy.txt) <(awk '{print $2}' marcy.txt) | column -t

Date Volume Volume Volume

2021-01-01 9827 8722 2762

2021-01-02 8372 2653 7622

2021-01-03 6399 9876 6523

2021-01-04 8726 2763 8725

2021-01-05 6882 8733 4265

The minor issue to fix is the “Volume” column name to reflect the name of the source data file:

paste -d' ' <(sed 's/Volume/Al/g' al.txt) <(awk '{print $2}' peggy.txt | sed 's/Volume/Peggy/g') <(awk '{print $2}' marcy.txt | sed 's/Volume/Marcy/g') | column -t

Date Al Peggy Marcy

2021-01-01 9827 8722 2762

2021-01-02 8372 2653 7622

2021-01-03 6399 9876 6523

2021-01-04 8726 2763 8725

2021-01-05 6882 8733 4265

While not very complicated, this is a bit tedious and you might be tempted to do this manually in a text editor or a spreadsheet application. But, what if you have a bunch of folders with potentially hundreds of such files that need to be merged?

Here’s the same method as described above, but now incorporating the find command. I added an extra file just to illustrate the point. Imagine if you had not four but four hundred files – try doing that by hand in a reasonable amount of time and without making any mistakes!

tmpscript=$(mktemp)

chmod u+x ${tmpscript}

echo -n "paste -d ' ' <(sed 's/Volume/$(basename $(find ~/datafiles -name "*\.txt" | head -1) | awk -F'.' '{$NF=""; print $0}' | sed 's/[[:alpha:]]/\u&/')/g' $(find ~/datafiles -name "*\.txt" | head -1)) " > ${tmpscript}

find ~/datafiles -name "*\.txt" | tail -n +2 | while read i; do echo -n "<(awk '{print \}' ${i} | sed \"s/Volume/$(basename $i | awk -F'.' '{$NF=""; print $0}' | sed 's/[[:alpha:]]/\u&/')/g\") "; done >> ${tmpscript}

eval ${tmpscript} | column -t

/bin/rm -f ${tmpscript}

Date Al Marcy Peggy Steve

2021-01-01 9827 2762 8722 6522

2021-01-02 8372 7622 2653 7725

2021-01-03 6399 6523 9876 1254

2021-01-04 8726 8725 2763 9272

2021-01-05 6882 4265 8733 3428

This all works just fine as long as the key columns in all of your data files align perfectly. But this rarely happens in real life. Let’s say we have three data files that look like this:

| al.txt | peggy.txt | marcy.txt |

Date Volume 2021-01-01 9827 2021-01-02 8372 2021-01-04 8726 2021-01-05 6882 2021-01-06 2435 | Date Volume 2021-01-01 8722 2021-01-02 2653 2021-01-04 2763 2021-01-05 8733 | Date Volume 2021-01-02 7622 2021-01-03 6523 2021-01-04 8725 2021-01-05 4265 |

If you apply the previous method, you will get garbage:

paste -d' ' <(sed 's/Volume/Al/g' al.txt) <(awk '{print $2}' peggy.txt | sed 's/Volume/Peggy/g') <(awk '{print $2}' marcy.txt | sed 's/Volume/Marcy/g') | column -t

Date Al Peggy Marcy

2021-01-01 9827 8722 7622

2021-01-02 8372 2653 6523

2021-01-04 8726 2763 8725

2021-01-05 6882 8733 4265

2021-01-06 2435

What we really need is to align these files on the “Date” field and merge those lines where dates match. This is well beyond what paste or pr can do. But there’s join. Let’s try using it on the first two files:

join -j 1 -o 1.1,1.2,2.2 al.txt peggy.txt | column -t Date Volume Volume 2021-01-01 9827 8722 2021-01-02 8372 2653 2021-01-04 8726 2763 2021-01-05 6882 8733

As you can see, January 6 line from al.txt has been dropped because there is no corresponding data point in peggy.txt. Right now I am not going to worry about the “Volume” column names – it just takes sed to fix that and we have bigger fish to fry (but I’ll come back to this later).

The 1.1,1.2,2.2 bit needs to be understood. The 1.1 refers to the first field of the first file. It is also the key field that needs to be matched in both files. The 1.2 is just the second field of the first file. The 2.2 is the second field of the second file. Sounds simple, but there’s gonna be more later.

Unfortunately for us, join can only join two files and we have three. So, the approach is to join the first two and use that as the first “file” for the second join:

join -j 1 -o 1.1,1.2,1.3,2.2 <(join -j 1 -o 1.1,1.2,2.2 al.txt peggy.txt) marcy.txt | column -t Date Volume Volume Volume 2021-01-02 8372 2653 7622 2021-01-04 8726 2763 8725 2021-01-05 6882 8733 4265

Now only three rows remain that have matching dates across all three files. In this case, 1.1,1.2,1.3 are the first three fields from the output of the inner join command, while 2.2 is the second field of the third file (marcy.txt).

Just as easily we could’ve redirected the output of the first join to a temporary file and then joined that file with marcy.txt, instead of concatenating the two commands. However, the less you use the filesystem, the faster your scripts will run.

Just for the hell of it, let’s add the fourth file:

join -j 1 -o 1.1,1.2,1.3,1.4,2.2 <(join -j 1 -o 1.1,1.2,1.3,2.2 <(join -j 1 -o 1.1,1.2,2.2 al.txt peggy.txt) marcy.txt) steve.txt | column -t Date Volume Volume Volume Volume 2021-01-02 8372 2653 7622 7725 2021-01-04 8726 2763 8725 9272 2021-01-05 6882 8733 4265 3428

We can also use this with the find command if we have a large number of files in various folders that need to be merged in this way.

tmpfile=$(mktemp)

chmod u+x ${tmpfile}

k=2

j="1.1,1.2"

echo -n "join -j 1 -o ${j},2.2 $(find ~/datafiles2 -name "*\.txt" | head -${k} | xargs)" > "${tmpfile}"

(( k = k + 1 ))

j="${j},1.${k}"

find ~/datafiles2 -name "*\.txt" | tail -n +${k} | while read i; do

echo "join -j 1 -o ${j},2.2 <($(cat ${tmpfile})) ${i}" > ${tmpfile}

(( k = k + 1 ))

j="${j},1.${k}"

done

eval "${tmpfile}" | column -t

/bin/rm -f "${tmpfile}"

Date Volume Volume Volume Volume

2021-01-02 8372 7622 2653 7725

2021-01-04 8726 8725 2763 9272

2021-01-05 6882 4265 8733 3428

This leaves just the pesky issue of the column headers. At this point, it is easier to simply modify the source data files to replace the “Volume” header with the one derived from the filename:

find ~/datafiles2 -name "*\.txt" | while read i; do

sed -i "s/Volume/$(basename "${i}" | awk -F'.' '{$NF=""; print $0}' | sed 's/[[:alpha:]]/\u&/')/g" "${i}"

done

tmpfile=$(mktemp)

chmod u+x ${tmpfile}

k=2

j="1.1,1.2"

echo -n "join -j 1 -o ${j},2.2 $(find ~/datafiles2 -name "*\.txt" | head -${k} | xargs)" > "${tmpfile}"

(( k = k + 1 ))

j="${j},1.${k}"

find ~/datafiles2 -name "*\.txt" | tail -n +${k} | while read i; do

echo "join -j 1 -o ${j},2.2 <($(cat ${tmpfile})) ${i}" > ${tmpfile}

(( k = k + 1 ))

j="${j},1.${k}"

done

eval "${tmpfile}" | column -t

/bin/rm -f "${tmpfile}"

Date Al Marcy Peggy Steve

2021-01-02 8372 7622 2653 7725

2021-01-04 8726 8725 2763 9272

2021-01-05 6882 4265 8733 3428

Now if you re-run the last join example you will have the “Volume” headers replaced by the correct names.

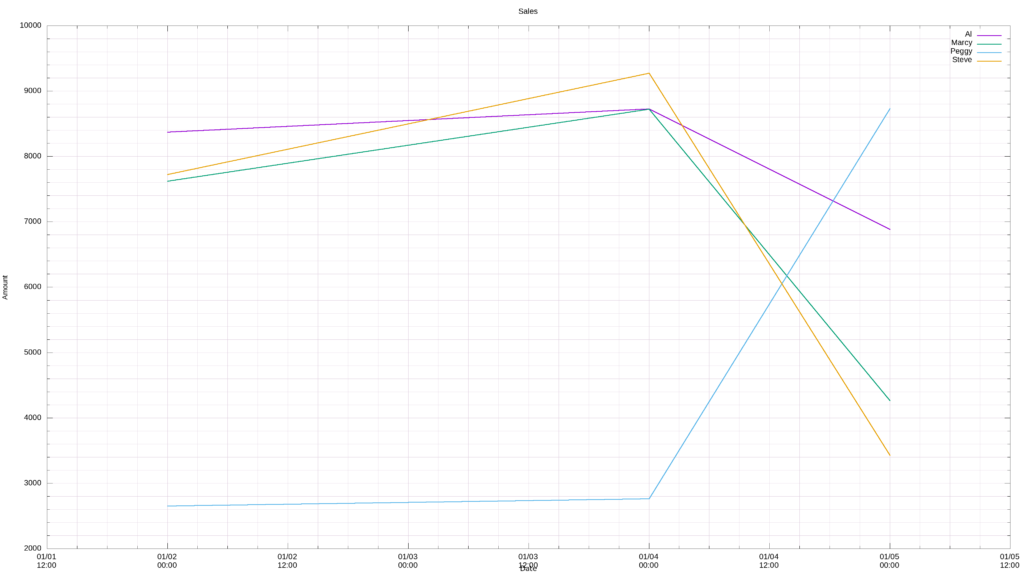

You may be thinking, this is all nice and very convoluted, but how is it useful? Well, for one, having all your data in one file in a consistent format allows for easier charting. Here’s a gnuplot timeline chart of the output from the last example above:

gnuplot -e "set title 'Sales';

set offset 1,1,1,1;

set autoscale xy;

set mxtics; set mytics;

set style line 12 lc rgb '#ddccdd' lt 1 lw 1.5; set style line 13 lc rgb '#ddccdd' lt 1 lw 0.5;

set grid xtics mxtics ytics mytics back ls 12, ls 13;

set terminal png size 3840,2160 enhanced font '/usr/share/fonts/truetype/liberation/LiberationSans-Regular.ttf,22';

set output '/mnt/c/zip/sales.png'; \

set style data labels;

set xdata time;

set xlabel 'Date' font '/usr/share/fonts/liberation/LiberationSans-Regular.ttf,20';

set ylabel 'Amount' font '/usr/share/fonts/truetype/liberation/LiberationSans-Regular.ttf,20';

set timefmt '%Y-%m-%d';

plot \

'${logfile}' using 1:2 title '$(head -1 ${logfile} | awk '{print $2}')' with lines lw 3, \

'${logfile}' using 1:3 title '$(head -1 ${logfile} | awk '{print $3}')' with lines lw 3, \

'${logfile}' using 1:4 title '$(head -1 ${logfile} | awk '{print $4}')' with lines lw 3, \

'${logfile}' using 1:5 title '$(head -1 ${logfile} | awk '{print $5}')' with lines lw 3"

More specific to sysadmin work, if you have an active-active application cluster, you may need to see if certain errors that appear on both cluster nodes ever align in time.

Another scenario: certain performance monitoring tools can show you this or that system parameter – but not this and that at the same time. So you end up with multiple timestamped log files that need to be mashed together.

If you want to see a practical example of the join command being used to process atop log, head over here.

Experienced Unix/Linux System Administrator with 20-year background in Systems Analysis, Problem Resolution and Engineering Application Support in a large distributed Unix and Windows server environment. Strong problem determination skills. Good knowledge of networking, remote diagnostic techniques, firewalls and network security. Extensive experience with engineering application and database servers, high-availability systems, high-performance computing clusters, and process automation.